Well Painted Places

A profile of Nathan Cann by Kara Au

In February of 2020, one month before the world would be engulfed by the coronavirus, Nathan Cann embarked on a journey to the Magdalen Islands. A French-speaking archipelago in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, it sits isolated from the province of Quebec to which it belongs. Visited only by plane or ferry, many of its inhabitants work seasonally in fishing, mining, and tourism—in the winter, they warm their bodies with ale.

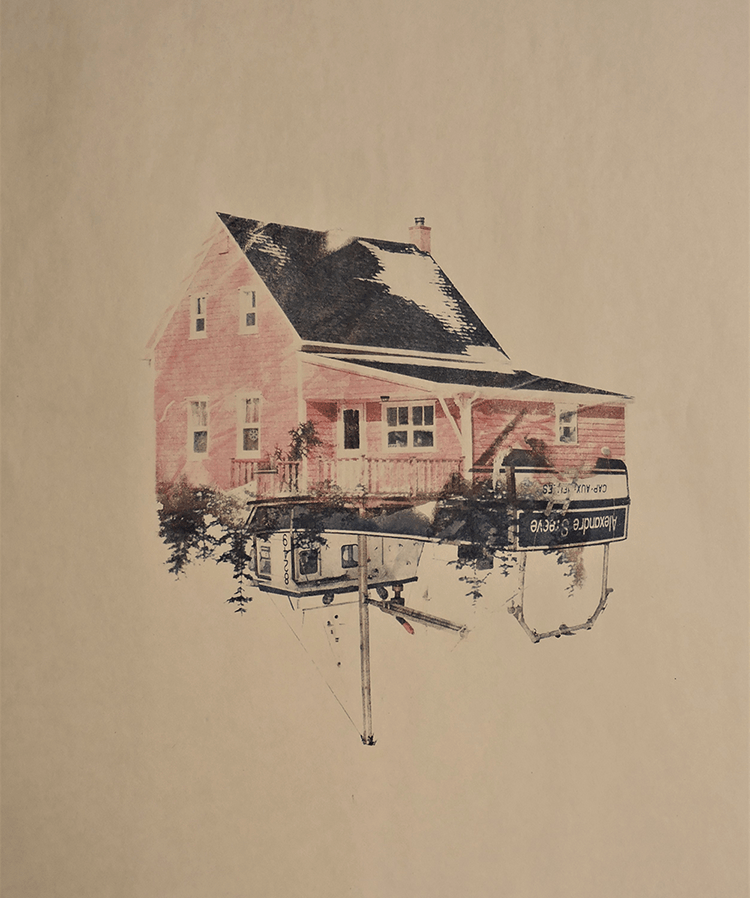

Cann arrives at one of the most inhospitable times of the year, some of the islands becoming inaccessible due to the harsh snowstorms. He notes that upon his arrival he is greeted by well-painted places—well-kempt houses richly adorned in radiant colours. Residing on Cap-aux-Meules, the most populated island in the archipelago, he peers outside the window of his room and sees nothing but the blinding whiteness of snow moving at light speed. The frigid winds pelt snow and ice against the siding, but the colours act like warding amulets to protect the people inside and enliven those outside.

Nathan Cann, Pink (2020). Monoprint, acetone and xylene photo transfer type, 20” x 24”. Courtesy the artist.

Despite the clear dangers, Cann gets into his car and drives precariously to the local microbrewery, À l'abri de la Tempête (which roughly translates to “shelter from the storm” in English). Upon arrival, he sees that many of its inhabitants have commuted via snowmobile. They handle the weather with casual disregard; despite the harsh conditions, the Island’s people live with the storm as a natural colleague.

Cann has arrived because he is in seek of something. In going to the Magdalens, he is in search of its haunting. Not ghosts or possessed buildings, but something that draws and ties its inhabitants to ultimately stay in a place far removed from the mainland. In Mi’kmaq, the Magdalens are called “Menagoesenog” or “islands swept by the surf.” It has over 400 recorded shipwrecks in its history, some survivors choosing to settle. The islands have a history of colonization while also serving as a home to victims from Le Grand Dérangement, the mass expulsion of Acadians from some Maritime provinces by the British in the mid-1700s. The islands themselves are experiencing increased erosion and heightened temperatures leading to less protection in the winter on top of rising water levels creating washouts.

Still, its people choose to stay, using their well-painted homes like guiding beacons. Cann sees this light from the distance; by searching for the hauntings, it feels like he is seeking avenues for hope. By tracing histories, landmarks, and symbols that draw inhabitants to form communities, he also uncovers the struggles that bind its people together, finding strength not just through unending optimism, but by weathering the storms ahead. There is no conclusion, no ritual to exercise, purify, or save the Magdalens, the only choice being to live day-by-day.

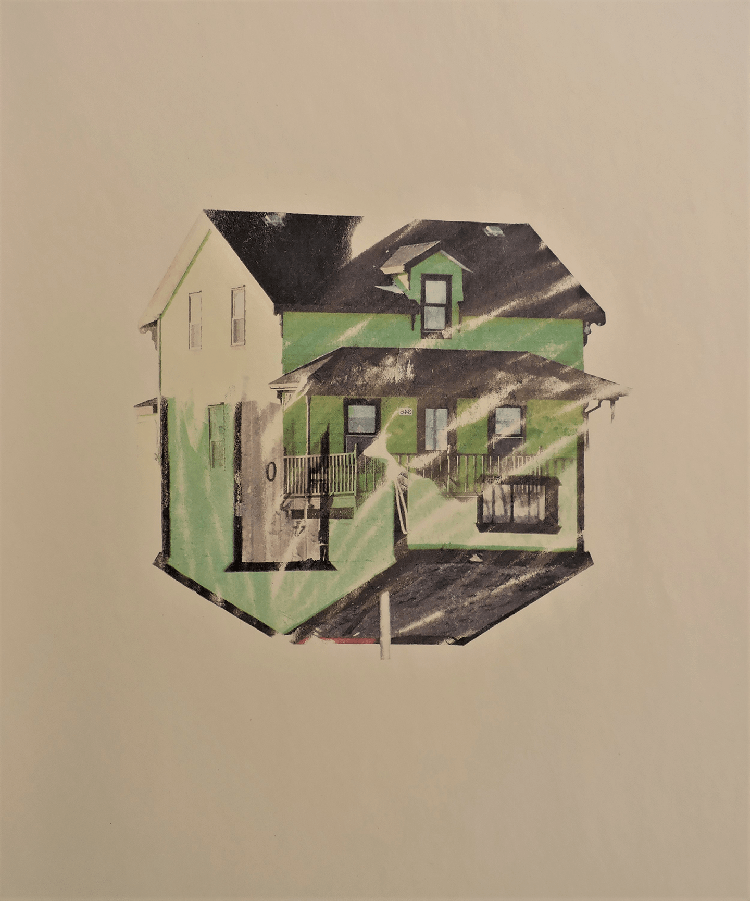

Nathan Cann, Green (2020). Monoprint, acetone and xylene photo transfer type, 20” x 24”. Courtesy the artist.

Arriving to complete his residency project, Colis suspect (French for suspicious package), with the local contemporary art organization, AdMare, Cann did not know that it would be his final journey before the World Health Organization would announce a global pandemic. In March of 2020, New Brunswick would begin to feel the effects of the coronavirus. It would fundamentally change how we communicate and engage with each other as we scramble to figure out our “new normal,” one with restricted barriers and greater distances. Companies would change their policies, including the approval to work from home to reduce the spread of a dangerously contagious virus. I would lose my job as funds halted in digital ad buying, only a skeleton crew remaining. It is during this time of unrest that I get to know Cann and his artistic practice as a printmaker.

First trained as a painter, Cann was introduced to printmaking by Erik Edson, now the Department Head of Mount Allison University in Fine Arts and professor in printmaking, drawing, and open media. Cann immediately makes the switch. While a patient mentor, Cann is an impatient practitioner—stretching canvas and waiting for paint to dry felt excruciatingly slow. Printmaking allowed him to work faster and thus experiment more. He doesn’t shy from failure, doesn’t obsess over keeping every little thing, and doesn’t make every print out to be some precious object: the process of him creating is as significant as the final product, and every week it seems like he is telling me about a new method that he is attempting just to see what happens.

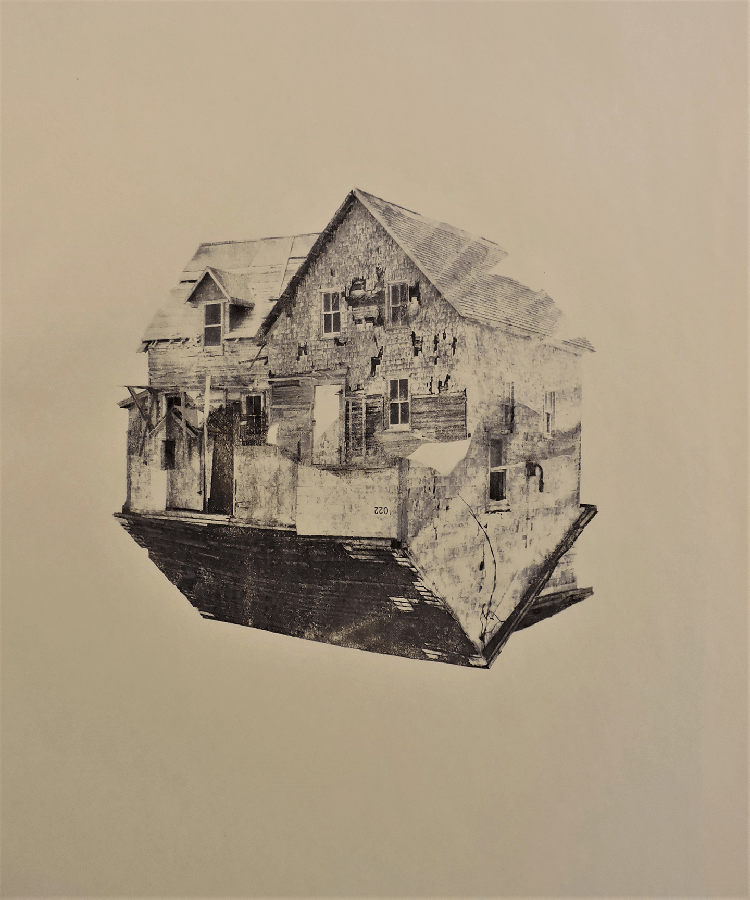

Nathan Cann, Ruin 1 (2020). Monoprint, acetone and xylene photo transfer type, 20” x 24”. Courtesy the artist.

Cann’s most well-known works are monoprints of old and occasionally dilapidated buildings against imagery of New Brunswick’s monopolized industries. Irving signs, refineries, and other signs of industrialization juxtaposed against homes, cities, forests, and churches display the embeddedness of private influences building the cultural narrative of labour and collective identity in the province. These image overlays float atop one another, producing spirit-like monoliths to express the hauntings that Cann has witnessed through his viewfinder.

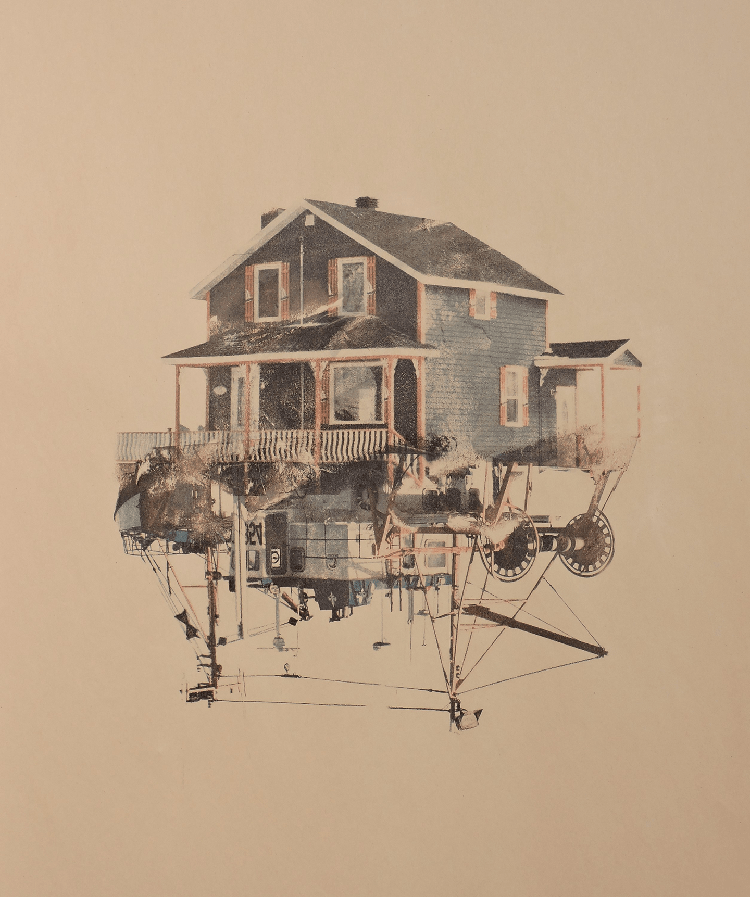

In his monoprints of the Magdalens, Cann links well-painted places and derelict buildings with fishing boats and symbols of ocean labour. In Blue (2020), a blue house with salmon trim lies right side up, blending into an upside down fishing vessel. However, the print can be orientated in any direction, displaying the co-dependent and circular nature of the archipelago’s people with the seas. While the waters provide sustenance and safe travel permitting visitors to come and go, not all is well in this relationship. Threats from global warming and unsteady weather patterns make the very waters that protect them serve as a threat to their way of living. Through workshops and guided exploration, Cann becomes acquainted with both the joys and anxieties of small island life.

Nathan Cann, Blue (2020). Monoprint, acetone and xylene photo transfer type, 20” x 24”. Courtesy the artist.

After Cann's return we arrange to have coffee. Every time I meet with him, we inevitably get off topic. I’ve given up on bringing notebooks or planning questions ahead of time. He has a disarming personality and treats strangers and friends the same, leading to much confusion on my end. As we sit at the café, I ask him to identify each passerby he greets, and it’s split between an actual name and “no idea.” None of it is an act. Yet, that same familiarity is what makes him an enigma, blurring friend and stranger beyond recognition. In this confusion, I don’t fully understand his motivations or why he chooses to create. I sip my coffee and ask Cann why he makes art; he shrugs calmly, saying he’s not sure, but it’s one of the only things in the world that he can do. It feels natural. We part ways and while I still don't understand, I know it's not a lie.

I later meet Cann at the Saint John Arts Centre and we both arrive sporting masks. Experiencing a sudden bout of anxiety, I check my purse to confirm that I didn’t forget my hand sanitizer. Times have changed. I have asked Cann to teach me printmaking so that I can better understand his practice. I am not an artist: I didn’t go to art school, I don’t know how to print, paint, cut, or assemble. I know next to nothing about colour, and I’ve spent an uncomfortable amount of my life envying the lives of professional artists. In no way did I glamourize the lifestyle of one of the most precarious careers you can have—as an artist, you are not free from constraint or the politics of art and funding organizations—but I envied each artist’s individual assertion that they would find a way to create for a living and stand behind the work that they make.

We start with linocut. Cann is the very opposite of elitist: he answers my questions with calm nonchalance while I observe him mixing magenta pigment for my first series of prints. I am mesmerized while listening to the soft sound of the metal spatula pressing into the glass countertop, spreading and gathering colour. It feels more like a therapy session than a workshop. As Cann focuses on his own project, I carefully push the Speedball cutter into a small, grey linoleum rectangle. My lines are jagged and clumsy and I barely miss my finger, but I’m satisfied looking at each indent I create. The final product is grossly novice but I still feel accomplished and look forward to our next session.

We try eco-printing using alum powder, vinegar, and coffee at our next scheduled meetup. I am not gentle with my hands; through excessive force, I iron over the newspaper covering foraged wildflowers, tearing it in the process. The final result is a moldy, fungal coloured splotch resembling a Rorschach test. I look over to Cann’s eco-print—it possesses delicate pastel hues, contrasting with his loud appearance: flamingo pink sunglasses with a matching button-up shirt. A somewhat deflating and humbling experience, through these workshops, I am given better context into the skill Cann brings to his art practice.

In my later conversations with Cann, after we have lived months into a global pandemic, I ask if being isolated on the Magdalens shared any similarities to isolation during the coronavirus. He looks up, thinking, then shakes his head. “Not really,” he says, because on the Magdalens, he still has a choice: stay home or brave the cold to meet others. These days, it feels like there is only one choice we can make, but life doesn’t seem simpler. The world feels more complex than ever. In spite of this, Cann looks relaxed. He is the enigma that is ready to greet whatever lies ahead. I don’t think that anything can fell his steady spirit.

Ice Field. Photo: Nathan Cann.